Edge of Eternities Vision Design Handoff, Part 1

Once vision design is done with a set and hands it off to set design, the lead designer of the set creates something we call a vision design handoff document. It walks the Set Design team through the larger goals, themes, mechanics, and structure of the set to help them better understand the work the Vision Design team did. I've published a bunch of them over the years, as they're always pretty popular. Here are the ones I've previously done:

- Throne of Eldraine (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Ikoria: Lair of Behemoths

- Zendikar Rising

- Original Zendikar (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Strixhaven: School of Mages (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Future Sight

- Original Innistrad

- Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Commander Legends: Battle for Baldur's Gate

- Original Ravnica

- Phyrexia: All Will Be One (Part 1 and Part 2)

- March of the Machine (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Wilds of Eldraine (Part 1 and Part 2)

- The Lost Caverns of Ixalan (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Outlaws of Thunder Junction (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Bloomburrow (Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3)

- Duskmourn: House of Horror (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Aetherdrift (Part 1 and Part 2)

- Khans of Tarkir (Part 1 and Part 2)

As with all my vision design handoff document articles, most of what I'm showing you is the actual document. My notes, giving explanations and context, are in the boxes below the text. This document, like most of them, was long enough that I've broken it into two parts.

"Volleyball" Vision Design Philosophy

Vision Design Team

- Ethan Fleischer (Vision Design Lead)

- Doug Beyer (Creative Lead)

- Andrew Brown (Set Design Lead)

- Jeremy Geist

- Mark Rosewater

- Megan Smith

Because Ethan Fleischer was the vision design lead, this document was written by him. While all vision design documents will go over similar aspects of the vision design process, there's no required way to structure the document, so Ethan's way of doing it is a bit different than mine. As most of the ones you've previously seen have been the ones I've done, it might seem like there's a specific way to structure them. There isn't. I just keep showing you the way I like to structure them. (For example, I'm a big fan of putting sample cards. Ethan is not.)

Ethan, like me, starts by introducing the Vision Design team. All of these people had a bio written by Ethan in my first Edge of Eternities preview article. Ethan accidentally left off the set's Worldbuilding team, so here they are:

- Miguel Lopez (Worldbuilding Lead)

- Laurel Pratt (Worldbuilding Assistant)

- Taylor Ingvarsson (Lead Art Director)

- Vic Ochoa (Art Director)

- Doug Beyer (Creative Lead)

- Sarah Wassell (Collectability Lead)

Magic in Space

"Volleyball" is the first of several planned sets taking place in a previously unseen part of the Multiverse: outer space. For this first outing, the setting is an entire solar system composed of five planets orbiting a black hole, along with dozens of moons and other astronomical bodies. Mana-powered spaceships travel between the planets in times of peace and war.

As the first entry into this new sub-brand of Magic, "Volleyball" serves as a foundation for future Magic sets. Structurally, the set emphasizes the identities of the five colors of Magic and how they express themselves in this new setting. We emphasized mechanical pathfinding, both for future in-universe space sets as well as for potential future Universes Beyond products. We also carved out a specific subgenre of science fiction, leaving other subgenres for future Magic space sets.

Magic often explores new settings, but the idea of going to space was a little more grandiose. What would going to space mean? Would we go to a known Magic plane, but leave the atmosphere? Or would this be its own area of the multiverse? We spent a lot of time talking this through and ended up deciding it should be the latter. In the end, we carved out an area at the edge of the Blind Eternities (hence the set's name).

For a quick aside on the Blind Eternities, we've spent a lot of time over the years being very vague about what exactly the Blind Eternities are. Using them in this context is us exploring some undefined space. The Sothera system borders the Blind Eternities, letting us explore the Blind Eternities without defining it. The Edge looks a lot like space.

Because this was something so different from what we usually do, we spent a lot of time setting ourselves up to do future space sets if needed. To do this, the arc planning team spent time mapping out the subgenres of stories in space (space opera, space horror, space exploration, and more). We then divided them into potential future sets. So, when Ethan talks about "planned sets," he's talking about the work we did to deliniate potential space sets, not implying that we have other space sets on an immediate schedule. The future of space sets will have a lot to do with the reception of Edge of Eternities. We're just letting you all know we did our homework if we ever decide we want to make more. In the past, Magic hasn't always done a great job of future-proofing returns to settings.

The "mechanical pathfinding" that Ethan talks about is the Vision Design team taking cues from the work the arc planning team did to make sure that we were staying in our lane and not designing things that potential future space sets of different subgenres might want to utilize. Despite this, Edge of Eternities was allowed to do a little teasing of what those future sets might be. When mapping out potential future space sets, we did talk a bit about what could happen if we end up doing a Universes Beyond set with a space component. We wanted to make sure that Edge of Eternities would help enable that if we needed it.

Space Opera

The space opera genre features colorful action-adventure stories of interplanetary or interstellar conflict, featuring a vivid and lush romanticism. The genre began with E. E. Smith's 1928 novel The Skylark of Space and is widely known these days through films such as Star Wars, the Star Trek movies, and Guardians of the Galaxy. A streak of nostalgia runs through space opera. Star Wars is a 1970s update of the Flash Gordon serials of the 1930s; Guardians of the Galaxy's spaceships recall paperback covers of the 1970s, and modern Star Trek continually mines the original material created in the 1960s.

Part of capturing the tone of a genre (or subgenre in the case of space opera) is having a good understanding of what makes that genre tick. Ethan is a big fan of research (he's been known to read many books on a topic before beginning design), so he spent some time looking into the history of space opera as a subgenre. He wanted to give any readers of this document a sense of how space opera media fits into pop culture.

The Sense of Wonder

The emotional core of classic science fiction lies in a sense of wonder. This is a somewhat slippery concept, but it could be described as a transcendent experience brought about by a sudden shift of perspective. One of the simplest and most effective ways to achieve this effect is through an increase in scale. E. E. Smith accomplished this in his Lensman series by opening each new book with the revelation that the monumental conflict described in the previous volume was but a minor skirmish in the actual war. By the end of the series, it was made clear that the central conflict of the setting could be measured in billions of years, was intergalactic in scope, and was led by immortal, godlike entities.

I talk a lot about the advantages of approaching design from different perspectives. For example, I usually talk about that through the lens of subject matter. An important delineator between the identities of sets is the vision design lead's perspective. Ethan and I are both fans of space opera media, but we approach it very differently. This paragraph gives a good insight into how Ethan thinks of the genre and demonstrates the emotional center to the set that Ethan designed.

"Volleyball" will achieve this sense of wonder through increase of scale in both its worldbuilding and its gameplay. The setting, an entire solar system populated by many planets and moons, each of which is big enough to hold an entire regular Magic plane, is grandiose in its scope. Future Magic space sets will move the camera back to reveal that this solar system is merely one of many such in the grand scheme of things.

Games using "Volleyball" cards will feature big, splashy, exciting plays, novel mechanics, and a literal increase in scale with new cosmic Magic cards, which are twice as big as regular cards and have a gameplay impact in proportion to their size.

Ethan is hitting upon what I consider the largest design challenge of space opera media: scale. An important part of what defines space opera is the sheer scope of the items at play. As Ethan says above, just one location in this set is significantly larger than places we've set entire Magic blocks before. One of the big challenges for Edge of Eternities was how to capture this shift in scope. It's a Magic deck, so items will be represented by cards, but how do you make a single card capture such a vast space? It's a pretty daunting task, but it was central to figuring out how to design a space opera set.

Mechanics

Cosmic Cards

These cards, twice as big as regular Magic cards, represent planets, stars, city-sized spacecrafts, and other spaceborne objects that are too large to be expressed as regular cards. They are distributed, folded in half, in booster packs. Each "Volleyball" booster pack contains one cosmic card in addition to the normal contents of a booster pack.

When we first came up with the idea of doing giant cosmic cards, the plan was to package them like we had done the giant cards from the Transformers trading card game. That game had a larger booster pack that fit the bigger card with a sub-booster that held the normal-sized cards. By the time of the vision design handoff, some work had been done to figure out whether or not we could actually print them. The idea Ethan is talking about here was that we would make double-sized cards that could be folded. That way they would fit into a normal-sized booster pack. The larger booster pack wasn't something all the printers could do, and Magic is large enough that we need to print it at numerous printers around the world.

We had two reasons for including one cosmic card per booster pack. First, we've learned that some amount of predictability is good, both helping the messaging of the set and creating expectation. When every set always comes with a particular known quantity, it increases excitement in the players. For example, players knew that every March of the Machine Draft Booster would include a battle card. Obviously, there will be randomness in which specific card they get, but including one in each booster pack would make that message clear. Second, a folded card weighs slightly more than two individual cards. So, if we didn't distribute cosmic cards in equal amounts, it would become apparent which booster packs had more cosmic cards. So, we planned for each booster pack to include one and only one cosmic card.

Goals

Cosmic cards should represent common concepts from science fiction that are large in scale and don't normally appear on Magic cards. They should be bigger than regular Magic cards to convey a sense of scale. They should include a graphic design element to justify the larger card size, as we don't want to fill the card's text box with twice as many words as a regular card.

The mechanic of cosmic cards should have sufficient design space that we can use cosmic cards in future sets, both in Magic Multiverse and Universes Beyond sets. They should be optimized to be able to represent iconic concepts in Magic card form.

Cosmic cards are the KSP mechanic of the set, and an important mechanic to get right for the sake of future sets. If cosmic cards come into conflict with other mechanics for space in the set, cosmic cards should win that fight. Cosmic cards will want rigorous testing to ensure that they're as appealing and intuitive as possible, as we want to commit to using them for years to come.

We spent a lot of time in exploratory design and vision design figuring out the solution to capturing scope. We landed on cosmic cards for a few reasons. One, the larger cards were just so good at capturing the sense of scale the set wanted. They depicted larger things, so they were physically larger. Bluntness is often a great tool for conveying concepts.

In playtests, we mocked up larger cards so we could get a sense of how they played. We wanted to understand the physicality of using them. How was the battlefield affected by having them in play? Did it feel right to tap them? How did it feel to have other cards to interact with them? We used that feedback to fine tune how other cosmic cards were being designed.

We also spent a lot of time trying to figure out what kind of text should go on those cards. As Ethan said, having a larger card was not meant to be an excuse to have more text. It was important to us that the design of cosmic cards was clean and elegant. In the end, we came up with something I was very proud of. They played well and had a very high "cool" factor.

The term KSP stands for "key selling point" and refers to an element of a product which we believe will encourage players to buy the set.

Mechanical Implementation

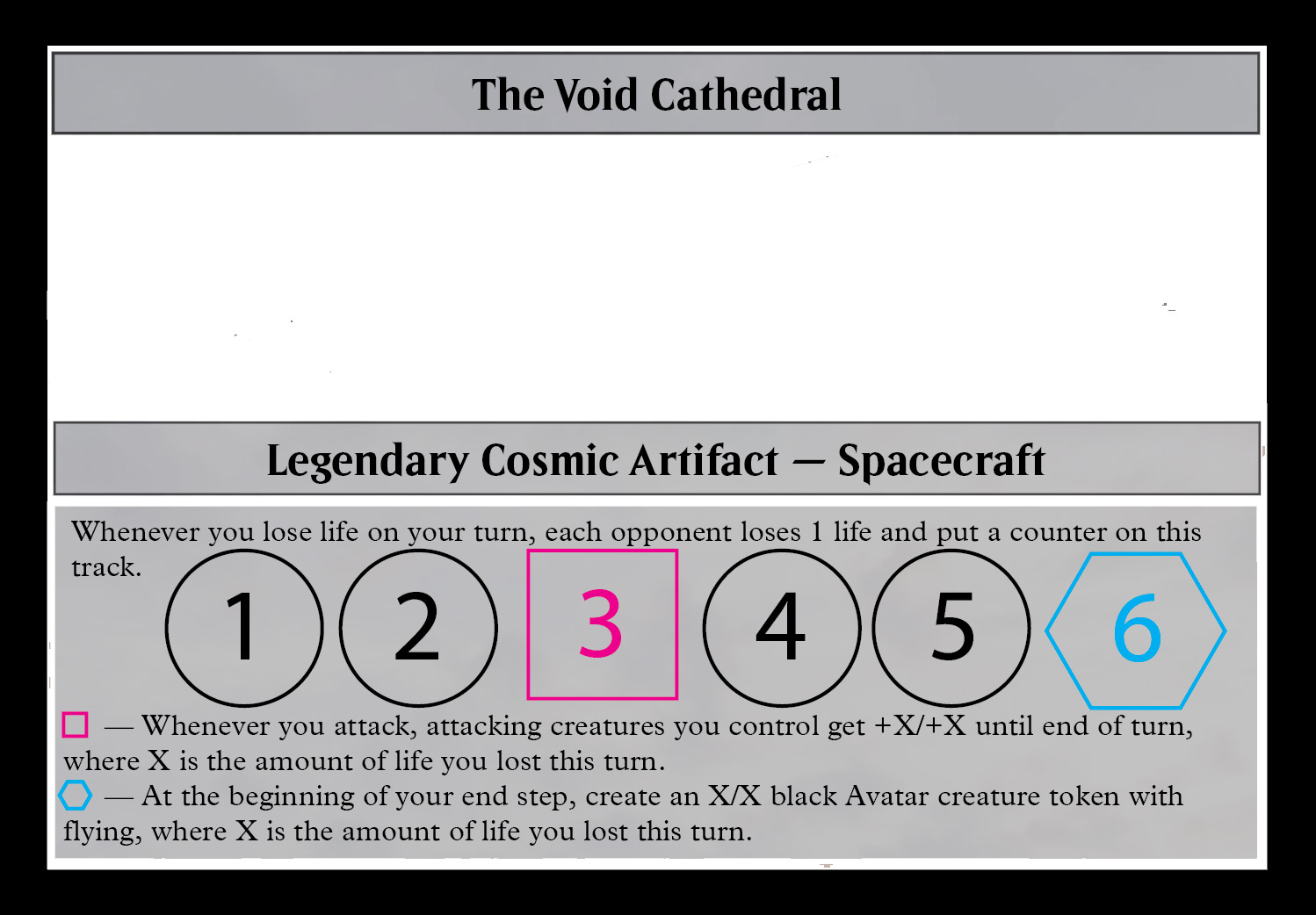

Cosmic is a supertype, and each cosmic card has one or more card types. These are most often artifacts (representing spacecraft) and lands (representing planets and moons), but cosmic enchantments and creatures are also present in the set.

In the handoff, we had a bunch of different cosmic cards. Besides Spacecrafts and Planets, we had enormous objects, giant space creatures, and huge space phenomena. When presenting a new idea during vision design, we want to branch out and try lots of different things. This allows set design to playtest, find which ones are working best, and then pull the rest out of the set. As a general rule, Vision Design wants to over-design, giving Set Design more material in finding what works.

Cosmic cards are arranged in a landscape format. Each features one or more tracks, each of which is composed of one or more nodes. Players add counters to fill in those nodes to unlock powerful abilities.

We set up cosmic cards horizontally because we wanted a track on them and preferred using a horizontal track. The plan was to make the track a big enough visual feature that a player could use a marker to keep track of its progression.

Cosmic cards are too large to be shuffled into players' decks, so they must be put onto the battlefield by regular Magic cards. This is accomplished by the "journey" keyword action. When a card instructs a player to "journey to COSMICNAME," if the player doesn't already control a permanent named COSMICNAME, they may put a card they own named COSMICNAME from outside the game onto the battlefield. If they don't put a card onto the battlefield this way, they scry 2.

The solution to the cosmic card issue mirrored a similar problem we had during the original Innistrad set's design. Because double-faced cards (DFCs) don't have a back, they aren't playable in anything other than a deck with opaque sleeves. While a lot of players play with opaque sleeves, not everyone does. Our original solution was to give each DFC and single-faced card that went in your main deck. When cast, the single-faced card would fetch the associated DFC.

The reason we didn't do that in the original Innistrad set was that the printers couldn't guarantee the pairs of cards would show up in the same pack. Even though it was over a decade later, our printers still couldn't guarantee it. We would later explore a version where cards fetch a subset of cosmic cards (often one of their color) and would adjust their as-fan to make sure they showed up in every pack.

Cosmic lands should have a mana ability or a mana-like ability, such as a cost reduction. However, cosmic cards should not naturally tap themselves. No cosmic should have a tap symbol in their activated abilities, and cosmic creatures should always have the vigilance keyword. We don't want players to often have to tap these oversized, landscape-oriented cards that are covered with counters. Mechanics such as improvise, which taps artifacts, should not be considered for sets that include cosmic cards.

One of the biggest lessons from playtesting with cosmic cards was that they were awkward to tap, so we built in a restriction to their design that they couldn't have a tap ability. There are a bunch of ways to create pseudo tap effects without having to ever actually tap the card, and we explored many of them in our cosmic card designs.

I'll finish this trip through the Edge of Eternities vision design handoff document next week. As always, I'm eager for any feedback you have about today's article, from anything about the set, the handoff document, or my commentary on it. You can email me feedback or contact me through social media (Bluesky, Tumblr, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter)

Join me next week for part two.

Until then, may you have fun exploring the universe of Edge of Eternities.